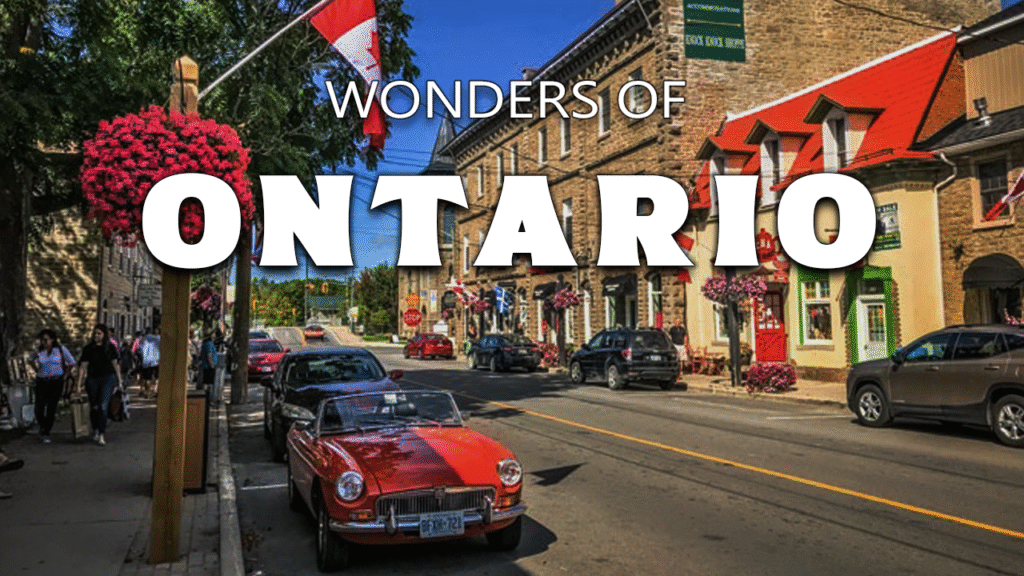

Discover the hidden wonders of Ontario through a journey that takes you far beyond the typical tourist paths to reveal 19 unforgettable destinations across this diverse Canadian province. My travel documentary showcases everything from the roaring beauty of Niagara Falls to the quiet edges of Georgian Bay’s pristine shores, giving you an authentic glimpse into Ontario’s natural landscapes, historic towns, and cultural riches.

I’ve captured these remarkable locations in stunning 4K footage to inspire your next Canadian adventure.

Watch my full Ontario travel documentary here:

The Natural Splendor of Niagara Falls

My journey through Ontario begins at the province’s most famous natural wonder – Niagara Falls. Standing at the edge, I felt the raw power of 6 million cubic feet of water thundering over the edge every minute, creating a roar you can physically feel in your chest. This natural phenomenon formed about 12,000 years ago when melting glaciers filled the Great Lakes, and it continues to carve through solid bedrock, moving backward approximately 30 cm each year.

The Canadian side offers the most breathtaking view with the horseshoe-shaped falls spanning 670 meters wide. What makes this experience truly magical is the perpetual mist rising hundreds of feet into the air, visible from miles away. When sunlight pierces through, it creates dancing rainbows across the churning waters below. At night, the falls transform into a colorful light display that shifts and shimmers against the darkness.

Indigenous peoples called this place “Onguiaahra” (the thundering waters) and recognized its spiritual significance thousands of years before European explorers arrived. Today, millions of visitors from around the world make the pilgrimage to witness this spectacular site, just as early travelers would journey for weeks to experience its wonder.

Toronto: Canada’s Vibrant Metropolis

Heading north from Niagara, I explored Toronto, Canada’s largest city that pulses with energy from its diverse mix of cultures and neighborhoods. Nearly half of Toronto’s residents were born outside Canada, creating one of the most diverse urban centers in the world. As I walked the streets, I heard conversations in over 140 languages and discovered foods, festivals, and traditions from across the globe.

The iconic CN Tower defines Toronto’s skyline, standing tall against a backdrop of gleaming skyscrapers. When completed in 1976, it held the title of world’s tallest freestanding structure for over three decades. I took the opportunity to walk on the glass floor 342 meters above ground – a heart-racing experience! For the truly brave, the EdgeWalk offers a chance to circle the tower’s exterior while suspended by a harness.

In the Entertainment District, I found Broadway-caliber shows in historic theaters lighting up King Street each night. Just steps away, the Distillery District’s Victorian-era buildings house art galleries and boutique shops on cobblestone streets. What was once the largest distillery in the British Empire now serves as a car-free cultural hub, creating a fascinating contrast between modern entertainment venues and preserved industrial architecture.

Toronto constantly reinvents itself with each generation while honoring its past. Sleek waterfront developments now stand where factories once dominated the shoreline, and new Canadians continue to shape neighborhoods with their unique contributions to the city’s identity.

The Garden City and Welland Canal

St. Catharines

Returning to the Niagara Peninsula, I visited St. Catharines, aptly nicknamed the “Garden City.” The city maintains over 1,000 acres of parkland, including gardens that bloom from April through October. The microclimate, moderated by sitting between two Great Lakes, creates temperatures warm enough for tender fruit trees.

The original Welland Canal once ran right through downtown. When ships moved to the newer canal, the city transformed the old route into a recreational waterway. Now people jog where schooners once sailed, and the old lock walls support restaurants and shops.

Martindale Pond hosted rowing events for the 1999 Pan-Am Games. In winter, this human-made lake freezes into a calm stretch of ice where skaters trace slow arcs through morning mist, transforming what was once a rowing course into a quiet stage for blades and ballet, framed by snow and low winter light.

Welland Canal

Following the path of commerce and engineering, I reached Welland, where the canal cuts across the Niagara Peninsula, lifting ships 327 feet between Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. Eight locks accomplish what Niagara Falls makes impossible—a water route through the Great Lakes to the Atlantic.

At Lock 3, right in the city, a viewing platform lets you stand eye-level with ship bridges. I watched as a 740-foot lake freighter took about 45 minutes to transit a lock. The gates closed, water flowed in from above, and 30,000 tons of steel rose like an elevator. The ingenious system uses no pumps, just gravity and careful engineering.

Port Colborne: Where Industry Meets Nature

Where the canal meets Lake Erie, Port Colborne stretches along a quieter, warmer shore. Here, the waves are smaller, the horizon lower, and the water takes on a softer hue in late summer light. Nickel Beach lies just east of the canal’s mouth, tucked behind a curve of dunes and grassy bluffs.

What I found fascinating was how locals drive their cars right onto the fine, pale sand, unloading chairs and umbrellas like it’s a private slice of ocean. The lake stays shallow for yards out, warming quickly under the sun.

Just beyond the beach, the skyline changes dramatically. Tall grain elevators and freighter cranes mark the entrance to Port Colborne’s working harbor. This is one of the last places in Ontario where industry and nature still share the same shoreline. Ships from around the Great Lakes dock here, unloading cargo just a few hundred meters from where kids build sandcastles. Port Colborne balances opposites—leisure and labor, stillness and motion—and its beauty lies in this contrast.

The Waterfall City of Hamilton

Following Lake Ontario’s western shore, I discovered that Hamilton has over 100 waterfalls within its boundaries—more than any other Canadian city. They exist because the city sits where the Niagara Escarpment meets Lake Ontario, creating a 300-foot elevation change. Streams flowing off the escarpment have no choice but to drop.

Albion Falls spans 62 feet wide and drops 62 feet, a perfect square of falling water. The cascade has carved a bowl in the soft shale below, creating pools deep enough to swim in during high water. While the city has built viewing platforms, locals know the unmarked trails that lead behind the falls.

Tews Falls, just upstream, drops 134 feet in a narrow ribbon, making it the tallest in the region. It spills from the edge of the escarpment into a deep gorge by Spencer Creek, framed by layers of exposed rock and dense greenery in summer. The trail nearby leads to scenic overlooks where you can feel the cool spray drifting up from below.

Lakefront Communities: Mississauga and Oakville

Mississauga

Moving east along the lake’s curve, I found that Mississauga’s lakefront extends for 9 miles along Lake Ontario, though much of it remains industrial. The city has been reclaiming sections for public use, building parks and trails that connect neighborhoods to the water.

Port Credit began as a trading post where the Credit River meets the lake. The river got its name from French traders who extended credit to indigenous trappers. Now the harbor shelters hundreds of pleasure boats. The lighthouse, rebuilt after a fire in 1991, stands where beacons have guided boats since 1804.

The Waterfront Trail runs through the city, part of a 900-mile route that will eventually circle Lake Ontario. In Mississauga, it passes through parks, crosses river mouths on bridges, and occasionally detours inland around private property. Following it gave me glimpses of how the shoreline looked before development—marshy river mouths, gravel beaches, and bluffs carved by waves.

Oakville

Between Mississauga and the Golden Horseshoe’s heart, Oakville maintains the feel of a lake town despite growing to over 200,000 people. The old downtown, called Kerr Village, keeps buildings to three stories. Mature trees arch over the streets, and you can walk from antique shops to the harbor in 5 minutes.

Sixteen Mile Creek cuts a deep valley through town on its way to the lake. The creek got its name from its distance from the western end of Lake Ontario. Salmon run up the creek each fall, jumping rapids in Lion’s Valley Park while crowds gather to watch.

Bronte Harbor at the mouth of Twelve Mile Creek stays busy all summer with sailors heading out to race or cruise. The outer harbor protects an inner basin where boats tie up three deep on busy weekends. The lighthouse at the harbor entrance still operates, though GPS has replaced it for most navigation.

Natural Wonders: Cheltenham Badlands to Tobermory

Cheltenham Badlands

Heading northwest from Toronto’s urban sprawl, I was surprised to find the Cheltenham Badlands—they look completely wrong for Ontario. Red hills stripped of vegetation, carved into sharp ridges and deep gullies. Poor farming practices in the 1930s exposed the Queenston shale underneath, and erosion did the rest.

Now, these 36 acres of Mars-like terrain draw photographers who come for the way late afternoon sun lights up the iron oxide in the rock. The badlands sit in the larger Caledon region where the Niagara Escarpment creates a rumpled landscape of hills and valleys. The Credit River cuts through it all, running cold and clear enough to support wild brown trout.

Tobermory

Following the Bruce Trail north, I reached Tobermory at the tip of the Bruce Peninsula where the land simply runs out. Tobermory itself is just a few streets wrapped around two harbors, but those harbors hold some of the clearest water in the Great Lakes. Standing on the dock, I could count individual rocks on the bottom 40 feet down.

The Grotto formed when waves found a weak spot in the dolomite cliffs and carved inward. Now it’s a cave half-filled with water that glows blue-green on sunny days. Getting there means scrambling down loose rocks and squeezing through gaps in the cliff face.

Bruce Peninsula National Park protects 60 square miles of cliff, forest, and shoreline. The coastal trail runs along the edge of the Niagara Escarpment where 400-million-year-old rock drops straight into Georgian Bay. In some places, the trail passes through forests so thick the ground stays dark at midday. In others, you walk on bare limestone following crevices across moonscape terrain.

Big Tub Harbor got its name from its round shape and steep sides. Now it shelters both pleasure boats and the glass-bottom tour vessels that cruise over the wrecks. The water stays so clear because it’s cold—even in August, the temperature rarely climbs above 60°F.

Fathom Five National Marine Park protects 22 known shipwrecks. The shallow ones, some just 20 feet down, date from the 1800s when sailing ships tried to navigate these waters without modern charts. The wood has turned black with age, but you can still see deck planking, ribs, and sometimes anchors lying where they fell.

Georgian Bay: The Land of 30,000 Islands

Beyond Tobermory’s harbor stretches one of the most remarkable waterscapes in North America. Georgian Bay contains somewhere around 30,000 islands. The exact count depends on what you call an island versus a rock with a tree on it. The bay itself stretches 120 miles from north to south, big enough to generate its own weather systems.

The islands range from bare granite knobs that disappear in high water to substantial chunks of land with forests, meadows, and freshwater ponds. Some support single cottages passed down through families for generations. Others remain empty except for the cormorants that nest on their windward shores.

The Group of Seven painters came here in the 1920s, drawn by the way wind shapes the white pines and how pink granite meets blue water. A.J. Jackson painted the same stretch of shore dozens of times, trying to capture how the light changes through the seasons. Today you can stand in the same spots and see why they kept coming back.

Northern Ontario: Parry Sound to Manitoulin Island

Parry Sound

Along Georgian Bay’s eastern shore, Parry Sound wraps around a protected bay that has sheltered boats for generations. The town grew around lumber mills that processed white pine from the surrounding forests. Those forests are long gone, replaced by second-growth hardwoods, but the harbor remains busy with boats heading out to explore the 30,000 islands.

From town, you can boat to islands where the only signs of humans are the navigation markers on offshore shores. The outer islands face open water that stretches to Michigan, 200 miles away. When storms blow in from the west, waves crash against granite shores with enough force to throw spray 50 feet inland.

Muskoka

Inland from Georgian Bay’s rocky shores, Muskoka’s lakes interconnect like a liquid puzzle. Lake Muskoka flows into Lake Rosseau, which connects to Lake Joseph, all linked by rivers and human-made cuts. The region supports about 60,000 year-round residents, but that number triples each summer when cottage owners arrive.

The lakes formed when glaciers scraped hollows in the granite bedrock, then melted to fill them. The deepest spots reach down over 200 feet. The water stays clean enough that many cottagers still draw drinking water straight from the lake.

Manitoulin Island

Manitoulin Island stretches nearly 100 miles across Lake Huron, holding the title of the largest island in any freshwater lake on Earth. Its rugged shoreline and quiet bays give way to winding roads that pass through dense forest and open farmland where time seems to move a little slower.

Surrounded on all sides by Lake Huron’s deep blue waters, the island’s landscape feels remote and elemental. Small communities line the coast, and the lake is never far from view. Near the island’s eastern edge, the road climbs toward Whitefish Falls, where cliffs rise above a web of rivers, lakes, and forest. It’s one of the best places to see Manitoulin’s layered terrain from above—water, rock, and trees in every direction, blending into the vastness of the lake beyond.

Urban History: Sudbury, Kingston, and Ottawa

Sudbury

Leaving the islands behind, I ventured inland to Sudbury, which sits in a 40-mile wide basin created by a meteorite impact 1.8 billion years ago—the second largest known impact crater on Earth. The nickel and copper deposits that made the city’s fortune came from that cosmic collision.

For decades, smelter emissions killed most vegetation around the city, leaving bare black rock. Starting in the 1970s, the city began a regreening program. Volunteers have planted over 10 million trees. The transformation shows what’s possible when a community decides to fix past damage.

Ramsey Lake sits right in the city, big enough for sailboats and deep enough for lake trout. The city built Science North on the shore, housed in two snowflake-shaped buildings designed to blend with the rock outcrop they sit on. The facility includes a climate lab where you can experience -40°, the temperature where Celsius and Fahrenheit scales meet.

Kingston

Following the waters east toward the St. Lawrence, I found Kingston’s downtown built from limestone quarried from the same bedrock the city sits on. The stone gives the buildings a uniform gray color that turns golden at sunset. Many structures date from the 1840s when Kingston briefly served as Canada’s capital.

Fort Henry guards the entrance to the St. Lawrence River from its hilltop position. The British built it in the 1830s to defend against American invasion, with walls 10 feet thick, designed to withstand cannon fire that never came. Now students in period uniforms perform rifle drills for tourists.

East of the city, the St. Lawrence River widens and splits around the first of the Thousand Islands. The granite islands start small, just rocks with a few trees, but grow larger as you head downstream. Some hold single cottages, others support entire communities connected to the mainland by bridges.

Brockville and Ottawa

Where the river begins to reveal its island treasures, Brockville grew up where the Thousand Islands Parkway meets the St. Lawrence River. The town’s prosperity came from its position on the water route between the Great Lakes and the Atlantic. 19th-century merchants built elaborate homes on the hillside, each trying to claim the best river view.

Upstream from the islands, where two rivers converge, Ottawa stands as the nation’s capital. Queen Victoria chose this strategic location in 1857, transforming a lumber town into a political center. The stunning Gothic Revival buildings of Parliament Hill rise above the Ottawa River with limestone facades and copper roofs.

The historic Rideau Canal cuts through the heart of Ottawa—a 19th-century engineering marvel now recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site. Built as a military supply route after the War of 1812, it stretches 202 km to Kingston. Summer brings boats and cyclists to its waterways and pathways. Winter transforms the canal into the world’s largest naturally frozen skating rink, extending 8 km through downtown.

Full Circle: Lake Ontario’s Shores

Returning full circle to where my journey began, I was reminded that underlying all these shoreline communities lies Lake Ontario’s massive presence that shapes everything. Though it’s the smallest Great Lake, its 7,340 square miles still create an inland sea. The lake reaches 802 feet deep off Rochester—cold enough at depth to preserve wooden ships for centuries. Its surface area equals that of New Jersey.

The Scarborough Bluffs show what lies under much of Toronto: layers of sand and clay deposited by glaciers compressed into rock-like hardness. The bluffs rise 300 feet above the lake, eroding back about 3 feet per year. Houses built too close to the edge occasionally tumble down the slope.

Prince Edward County juts into the lake like a broken piece of the mainland. The island contains some of Ontario’s best beaches. Sandbanks Provincial Park protects the largest freshwater sand dune system in the world—mountains of sand up to 80 feet high, held in place by grasses that turn golden in fall.

Throughout my journey across Ontario, I’ve been amazed by the diversity of landscapes, from roaring waterfalls to peaceful island shores, from vibrant city centers to remote wilderness. This province offers so much more than most travelers ever see, with hidden gems around every corner for those willing to venture beyond the usual tourist spots.

If you enjoyed this virtual tour through Ontario’s wonders, please like the video and subscribe to my channel. I’d love to know where you’re watching from—drop it in the comments below. Who knows? Maybe my next documentary will take us to your part of the world.